- Home

- Michael Fleeman

Love You Madly Page 4

Love You Madly Read online

Page 4

The rest of what Bond found was to be expected. From what little paint had not been melted away, he could see this was once a purple Plymouth Voyager that still had the key in the ignition when it was set on fire. A glob of melted brass remained in the ignition cylinder. Broken glass located on the inside the driver’s door and the driver’s-side passenger door meant that these windows were rolled down during the fire. The other windows were likely closed and blasted out by the heat. From the burn patterns, the fire appeared to have started inside the van and was fueled by some form of accelerant, most likely gasoline.

Bond estimated the fire burned at 1,800 degrees, the same temperature at which a body is cremated. But the fact that the body was not reduced to ash meant that the fire burned only shortly: crematoria go for four hours. The torso, small bones, and some teeth discovered in the backseat had already been removed, but some parts remained. More teeth and small bones ended up near the front seat, having probably tumbled down there when the van was hoisted by the tow truck and hauled off. Bond packaged these to send to the coroner.

In Anchorage, the autopsy was conducted by Deputy Medical Examiner Susan Klingler. She inspected the contents of a bag shipped to her from Prince of Wales Island, what forensic pathologists call “cremains”: just thirty-three pounds of badly charred remains, with clothes, skin, and many bones burned away. There was enough of the jaw and teeth left to X-ray to try to identify the victim. Those X-rays were given to a forensic odontologist who compared them to Lauri Waterman’s dental X-rays collected by Chief See’s patrol officer. The odontologist concluded the identification of Lauri was “made to a certainty.”

Otherwise, the poor state of the remains limited Klingler as to what she could determine. X-rays found no obvious signs of violence—no broken knife tips or bullets. The neck had little tissue left, so Klingler couldn’t look for signs of strangulation. A test of the tissues for elevated levels of carbon dioxide—a sign Lauri was still alive and breathing at the time of the fire—was inconclusive. There was no soot in the small tubes of the lungs, but that also said little. Dying people usually don’t take deep enough breaths to get the soot all the way into the lungs.

In the end, all the autopsy could say was that Lauri was badly burned either before or after death. Any clues to how or where she died, or who may have killed her, couldn’t be gleaned by the examination. That would have to come from Sergeant Randy McPherron’s investigation.

Trooper Bob Claus searched Rachelle’s bedroom. It was a typical teenage girl’s room, not unlike his daughters’, with clothing on the floor, photos of friends on the walls, trophies on the shelves. Rachelle’s computer was taken away for later examination at an Anchorage electronics lab, but Claus found a stack of letters apparently written in Rachelle’s hand. The notes had writings about Rachelle’s relationship with one of her girlfriends and about Kelly Carlson, the former boyfriend she mentioned in her interview with McPherron. Again, it was the usual teen stuff, with nothing that could be linked to her mother’s murder.

One of the letters was different: it had been written on a word processor. It was from Jason Arrant, pleading with Rachelle to take him back.

Almost from the moment Doc Waterman had told him that Lauri was missing, Claus suspected that Jason had something to do with it. While sitting in his Expedition guarding the wreckage, Claus had gone through what he called “the logical progression of suspects,” rejecting those closes to the victim—Doc, Lauri, and Geoffrey—as the actual killers because all were away, but thinking how any of them could have still somehow been involved.

“I knew that Rachelle and Jason had a dating relationship; I knew that Lauri didn’t like that,” Claus recalled later. “I knew there was tension between those two people.”

Claus had briefed McPherron on this before they spoke to Rachelle, but it turned out to be Rachelle who brought up Jason, not the investigators.

Claus had a personal tie to Jason through Jason’s mother, who worked as a dispatcher for the Craig Police Department. For the rest of the case, Claus and other investigators had to proceed carefully so as not to tip off Jason, via his mother, to what they were doing. Though not close friends, Claus and Jason’s mother spoke every day at work and the trooper knew about her wayward son. He had left the island at least twice since graduating from high school but returned to live with his parents.

“He was an odd kid,” Claus would later recall. “I had been in the Marine Corps and he was going into the Marine Corps and had asked me advice on what do before he went. I basically told him to get in shape, to run a lot.” Jason never made it out of basic training. “He was too big and did not lose the weight in time,” said Claus.

Both Chief See and Sergeant Habib knew Jason, too, since his mother worked just a few feet away from them. Jason was not known as a dangerous or violent person, but he had had at least one brush with the law. When he lived in Hollis and was working as a school aide he faced complaints from a young girl. Claus investigated but never found any evidence.

When Rachelle started spending time with Jason over the summer, her mother objected, noting his age and apparent lack of direction. Lauri Waterman shared these concerns with Don and Lorraine Pierce.

“[Lauri and Rachelle] had their little squabbles, and they had their good moments too,” said Lorraine at trial, repeating what she told investigators. “They shared things like going to honor choir and Lauri chaperoned, and she was very proud of her daughter. And there were times where she wished that Rachelle wouldn’t act the way that she did or date the boys that she did; I know that they had little squabbles over it and major discussions. And Lauri, being the parent she was, would try to talk through and help her with her reasoning and help her make her decisions.”

The Watermans discussed this at least a half dozen times. “Lauri was very concerned that Rachelle was dating, first of all, a much older man, and secondly she was concerned that Jason might not have much of a goal in life,” Doc Waterman later recalled in court. “She was very concerned that her daughter would become involved to the point of marrying somebody who would not help her realize her potential.”

Doc Waterman couldn’t remember if he personally spoke to Rachelle about it. “Generally speaking, the day-to-day things with the children Lauri dealt with,” he said. “If she wanted a heavy hitter, she asked me to come in. I was the one who would ground her, that sort of thing. I don’t recall whether we talked jointly with Rachelle.”

Investigators reached out to Rachelle’s friends, asking if they thought she had been dating Jason or if they were casual friends. “I had heard rumors. I didn’t know anything officially,” her friend Amanda Vosloh recalled.

Although Rachelle never talked to Amanda about Jason, Amanda did see them together. Jason had been cast in the community theater production of The Importance of Being Earnest in the fall. Amanda was also involved, as was Rachelle, who was part of the lighting crew. Rachelle wasn’t required to go to the rehearsals on Tuesday and Thursday because she was on the technical crew, but she would come anyway, apparently just to see Jason. “She would come in after a practice and say hi to him and give him a hug,” Amanda recalled.

Stephanie Claus recalled seeing Jason with Rachelle when Rachelle worked at the T-shirt shop over the summer. “We went in once to invite Rachelle to go to the beach with us and Mr. Arrant was there,” said Stephanie. “They seemed to be getting along just fine. Rachelle was behind the counter doing whatever and Arrant was just sitting in a chair.” From their body language, Stephanie was aware that they were friends at least and perhaps something more, she said. “I kind of inferred that. But she had never confided in me about it.”

According to Bob Claus, it was not unusual on Prince of Wales Island for a girl of fifteen to be dating an older man. “In rural Alaska, sometimes that’s all there is,” he said. “There’s a saying here they put on women’s T-shirts: ‘The odds are good, but the goods are odd.’ It’s not uncommon for somebody in the twenty-somethin

g crowd to not be able to break out of the orbit and just be hanging around here, scratching out a living, socializing with the usual high school kids.”

Still, it would be more common to find a fifteen-year-old dating a nineteen- or twenty-year-old. “Rachelle was pushing that,” he said. “It was clear she was being disciplined for that. I sympathized with Lauri and Doc.”

Rachelle’s friends and family said she had had at least two boyfriends before Jason, both of them older. Her first love was Kelly Carlson. She was a fourteen-year-old high school freshman and he was a junior from another school when they met at a youth leadership conference in Craig. The event was called a “lock-in,” in which the kids were isolated in a building for two intense days of team-building activities. Kelly had grown up in a village called Point Baker on the northernmost tip of Prince of Wales Island. One of the most isolated communities in America, Point Baker has about three dozen residents and is accessible only by boat, the gravel roads ending miles away. At the time he met Rachelle, he had just moved to Thorne Bay.

After the conference, they kept in touch by e-mail, and when he was in Craig they’d hang out at the Voyageur Bookstore. It was Rachelle who made the first move, he told investigators, asking him out on a date after they’d known each other for about three months. They went to one of the only places on the island where young people could congregate: Papa’s Pizza in Craig.

They were boyfriend and girlfriend for about five months, chatting online when they couldn’t be together before the stress of their long-distance relationship and their age difference caused them to break up. Rachelle again took the initiative, dumping him, he said, in an e-mail while he was in summer school in Fairbanks in 2003.

Her next boyfriend was a Craig High School boy named Ian Lendrum who had arrived on the island in 2002. They met while walking home from school and started dating in the summer of 2003. Rumor had it that her problems with Ian started around the same time she met Jason. But in recent months, as Rachelle returned to school and her busy schedule, Jason seemed to have drifted out of her life—until Don Pierce saw him in the principal’s office that afternoon.

McPherron then discovered that Rachelle may have seen Jason again that day. After Rachelle got the news from Chief See about her mother’s van and went next door to the Pierces’ with her father, a worried Don Pierce called her friend Stephanie Claus to ask if she could be with Rachelle.

Stephanie came over, and the girls hung out there with their friend Amanda Vosloh and Don’s son Phillip Pierce, who is six months older than Stephanie. Despite the tumultuous events of the past twenty-four hours, Rachelle was back to acting “very normal,” recalled Stephanie, who was interviewed by police. “She was very calm and just like she’d always been.”

The subject of her missing mother hung in the air, but “Rachelle said she didn’t want to talk about it,” recalled Stephanie. “Phillip and Amanda and I didn’t push her. She explained that her mother’s van had been found on Monday and that she didn’t want to talk about it, that she wanted to leave the house and to do something fun to get her mind off of it.”

The trio sampled the few activities available to teens on a Monday night on Prince of Wales Island. They browsed at the Voyageur Bookstore in Craig, went to the boat harbor, then took a drive, with Phillip at the wheel of his sister’s car. They left Craig, went past the Viking Lumber Company sawmill, and headed toward Klawock, where the island’s only convenience store—the Black Bear Market—is located. “There’s not a lot of places to drive within the town,” Stephanie said.

Until now, Rachelle’s behavior seemed normal enough, her friends accepting that she wanted to get her mind off her troubles. But halfway to Klawock, Rachelle announced, “I need to take a crap,” and asked if they would stop at the Klawock school.

She went inside and emerged five or ten minutes later, saying she had seen Jason. She again made a crude remark, this time about how badly the bathroom now smelled and he’d have to clean it up, but it was OK because he was well paid as a janitor.

They turned around and went back to Craig, going into Papa’s Pizza, where Ian Lendrum worked, for about forty minutes before returning to the Pierces’ house.

The most provocative information came from Rachelle’s friend and volleyball teammate Katrina Nelson, who was on the trip to Anchorage. Katrina recalled that Rachelle borrowed her cell phone about four times, usually to call to her mother.

“She said she called ‘Red,’” said Katrina.

She didn’t know who Red was, but Katrina knew Jason Arrant had red hair, and she suspected it was him. So did Sergeant McPherron and Trooper Claus.

CHAPTER FOUR

Ian Lendrum was asleep when detectives knocked on his door at ten a.m. on Tuesday, November 16. Startled awake, Ian raced downstairs before he realized he wasn’t wearing a shirt. He went back upstairs to dress, then returned to the front door to let the investigators in. He started a pot of coffee to clear his head.

Ian was worried. The rumor sweeping the island was that police wanted to arrest Rachelle’s former boyfriend. At the time of Lauri’s murder, Ian fit that description. From the outset, he insisted to detectives, he had nothing to do with Lauri Waterman’s murder. He had always gotten along well with the Watermans, had remained friends with Rachelle even after they broke up, and had even been with her that week to help comfort Rachelle.

He said that on Sunday, the day Rachelle was to return from Anchorage, he called her house a couple of times but got no answer. It was unusual for Rachelle to be unreachable, so he finally went to the house in the evening and found Rachelle with her father.

“Me and her were downstairs and watched a movie,” he recalled later, recounting what he told investigators. “I just remember being really worried and stuff.” Rachelle, he said, seemed “distressed” and “looked like she was going to cry.”

He asked her what was wrong. “She just couldn’t speak. She was worried about things,” he said. “She said she had to go upstairs and make dinner for her dad.”

Only later did he find out that Rachelle’s mother was missing.

Investigators asked Ian about his history with Rachelle. He said it was uncertain exactly how long they were together—“Just seemed like forever,” he said—and he couldn’t pinpoint the date they broke up.

Ian had been part of Rachelle’s circle of friends who played the ultraviolent science fiction video game Halo and Dungeons & Dragons, first at the homes of Rachelle and Ian, then over the summer of 2004 at the computer store in Craig where Rachelle worked. Rachelle was the only girl among the D&D players, who included Ian, his friend John Wilburn, Jason Arrant, and Jason’s best friend—and the owner of the store—a six-foot-five-inch, 280-pound bearded giant named Brian Radel. The group took their game-playing seriously, each player assuming a fantasy identity as they immersed themselves in make-believe adventures.

“She was a thief,” Ian recalled, “Brian was a warrior, and Jason was a vampire, and I don’t remember what John was.” (John later said, “I myself prefer spell-casting roles.”) They would keep their characters for about two weeks, meeting sometimes daily over the summer, scarfing down pizza from Ian’s store, Papa’s Pizza.

The interview with Ian complete, detectives compared notes. In recent months Rachelle’s life had split into two—the D&D crowd on one side, the choir/sports girls on the other. While not unusual for a teenager to belong to more than one social clique, in Rachelle’s case the dichotomy seemed particularly stark. Her girlfriends knew little of Jason Arrant and even less of Jason’s friend Brian Radel.

Rachelle’s volleyball teammate Katrina Nelson told investigators she thought she had heard the name Brian but didn’t know if Rachelle had mentioned him or somebody else. Katrina couldn’t place the face. Rachelle’s parents knew even less. Detectives would find out that Lauri once visited the computer store over the summer while Brian was working there. Whether Lauri took notice of the big man wasn’t known. About a week later B

rian bought food from Lauri while she was working at a snack stand at a Fourth of July fair, but again, it wasn’t known whether she noticed him.

Bob Claus knew more. He remembered first seeing Brian Radel when Brian was ten years old. Brian’s father was a gunsmith who did work on the trooper’s shotgun. The Radel shop was in the family compound, a run-down homestead-type spread with children—apparently Brian and at least one sibling—running around dressed in camouflage. Claus seemed to recall the Radel children had been home-schooled and trained in military tactics. His lingering impression: “Think Deliverance.”

When Jason was older, he had been seen around town with Brian, the two big men hard to miss. Claus related his thoughts to McPherron. He didn’t know where Brian lived now, but the compound where he grew up was in Thorne Bay, not far from where the van was found.

“I was really concentrating on the two men,” Claus recalled. “What I saw were these two people were associated with Rachelle. She couldn’t have done this. But they could.”

McPherron agreed. “Because of Trooper Claus’s information regarding the problems between Lauri Waterman and Jason Arrant and the problems that it caused in the family, they seemed to be a very logical place to start,” he said. With the investigation stretched thin, McPherron called in two more detectives to find Jason Arrant and Brian Radel and try to get initial interviews to determine their whereabouts on the night of Lauri Waterman’s murder.

One phone call to Jason Arrant’s parents’ house brought him to the trooper post in Klawock. He arrived at noon on Wednesday, November 17, while the investigators were still speaking to Ian Lendrum and Rachelle’s friends and searching the Waterman house. He met with one of McPherron’s reinforcements, Trooper Cornelius “Moose” Sims, who flew in from the investigations bureau in Soldotna, south of Anchorage.

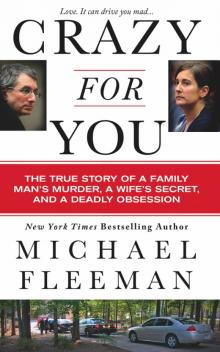

Crazy for You

Crazy for You Love You Madly

Love You Madly