- Home

- Michael Fleeman

Love You Madly Page 5

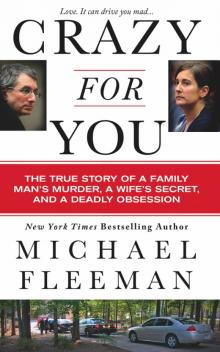

Love You Madly Read online

Page 5

Although he appeared voluntarily, Jason made it clear that he was not happy about what was going on. The same rumors troubling Ian Lendrum had reached Jason, no doubt sparked by Rachelle’s friends’ questions about him. Jason complained that the latest rumor was that he had already been arrested for the murder of Lauri Waterman, and nothing could be further from the truth.

In a brief conversation with Sims, Jason explained that, like Ian, he had once dated Rachelle, but they called it off to avoid problems with her family.

Sims asked him where he was at the time of the murder.

“Saturday night,” Jason said, thinking. “I believe that was the night I was out, hanging out with my buddy Brian. I stayed out in Hollis that night because I had had a few drinks and it was storming. I figured I should probably just crash instead of trying to drive home.”

Jason said the pair spent the day tooling around the island, leaving Brian’s place in Hollis at about two thirty p.m. Brian’s residence of late had been a room in the home of a retired sawmill worker named Lee Edwards. Jason drove his pickup because Brian didn’t have a vehicle. The two men arrived in “town”—what everybody called Craig—around four p.m. on Saturday; they bought munchies at the grocery store, stopped in a clothing shop, and hit other spots in Craig before driving to Klawock, then back to Hollis, where they got drunk and spent the night. Jason awoke around seven a.m. and drove to his parents’ house in Klawock, arriving around eight a.m.

Sims tape-recorded Jason’s statement and had a few more requests, to which which Jason readily agreed. He allowed Sims to take a DNA sample by swabbing the inside of his mouth, provided fingerprints and allowed for photos of his shoes to be taken for comparisons in case any footprints were found at the Waterman house or elsewhere.

Jason left the trooper post, then returned within minutes, saying he had just thought of something. He told Sims that Rachelle had once dated a boy named Ian Lendrum.

“I was there when she broke up with Ian,” Jason said, “and Ian got kind of scary.”

Finding Brian was also easy. Using the address provided by Jason, Trooper Dane Gilmore, who also had been sent in from Soldotna, and a trooper who worked with Claus in Klawock, Walter Blajeski, drove to Hollis and knocked on the door of Edwards’s house, a three-bedroom, woodstove-heated home that still appeared to be under construction. It was about 1:45 p.m. and Brian was there alone. As with Jason, the troopers asked Brian for his whereabouts the night of the murder and he gave an account similar to his friend’s: they had gone to stores in Craig and Klawock, then spent the evening at his place drinking. When Brian woke up the next morning, Jason was gone.

When asked about the murder of Lauri Waterman, Brian said it was the first he had heard of her disappearance. The island rumors hadn’t reached him out in Hollis. He said he didn’t have a television or read the papers, so if it had been reported, he’d have no way of knowing. (In fact, the case had not yet reached the media.) Brian agreed to having his mouth swabbed for a DNA sample, had his boots photographed, and posed for a picture of himself.

After the interview, Blajeski huddled with Gilmore. Blajeski had also long known Brian and was surprised at how he looked. Back at the trooper post, they showed the picture to Claus.

“Mr. Radel is a very distinctive man,” Claus later recalled. “He’s huge—large across the chest and shoulders, strong and tall, and goes close to three hundred pounds. He had a distinctive bushy unkempt reddish-brown hair and goatee … He was a sight to see walking down the street in Craig.”

The man looking up at him in the photo was somebody else. Brian had shaved off his hair and beard.

Under instructions from McPherron, the troopers didn’t press Jason or Brian on their alibis, any animosity with the Watermans, or, in Brian’s case, his new appearance. For now, McPherron wanted to establish—and lock in—their alibis while not letting on that they were under suspicion. That both men were big enough to easily overwhelm a woman of Lauri’s size didn’t escape notice. The plan was to double-check their alibis by interviewing the clerks at the stores they said they had visited and to speak with Lee Edwards. The detectives were also calling the airlines to confirm the travel accounts of Rachelle and Doc Waterman. Soon they’d set up follow-up interviews.

But before they could get back to Jason, Jason got back to them.

At five thirty p.m., Craig police received a call from the Klawock School near the trooper post. The dispatcher relayed the message to Claus.

“There is a man holding everyone inside the building,” the dispatcher said.

Sensing this had to be linked somehow to the Waterman case, Claus and McPherron made the short drive to the school, where the situation was considerably less dire than described. In the school office the investigators found the school’s janitor, Jason Arrant, trembling and crying.

The investigators turned on a tape recorder and asked what had happened.

“I went around to the side of the building so I could walk up the hill to the Dumpster,” he began, “and I hadn’t gone more than about ten steps and someone grabbed me from behind and got a handful of my hair and pulled my neck back and I felt a blade at my throat. He told me that if I didn’t stay away from Rachelle, there was going to be another accident. And while he was talking to me he was running the blade across my throat.”

Jason described the weapon as a serrated knife, and he showed the troopers a red mark on his throat left by the blade.

The two investigators searched the school and spoke to people. An electrician fixing the basketball scoreboard who had wandered into the parking lot to get his tools at the same time as Jason’s reported assault said he didn’t see anything. The principal, who was standing on the porch and had a good view of the parking lot at the time, also saw no attack. Claus and McPherron walked with Jason through his reenactment, looking for footprints or other signs of a scuffle, but could see no evidence other than the injury to his throat, which appeared superficial.

(At one point a man who lived nearby came out with a shotgun to assist the investigators, but he was sent home.)

Claus and McPherron were soon convinced that Jason had made the whole thing up. They allowed Jason to go home but knew that wouldn’t be the end of it. Jason would certainly tell his mother, the police dispatcher, who would be suspicious if the troopers didn’t file a report.

Claus called in a fake “Be on the lookout” for a man with the description given by Jason. But the real focuses of their investigation were Jason Arrant and Brian Radel. The one person still alive linking them was Rachelle Waterman. The investigators called her house to set up a follow-up interview. The questions this time would be more pointed.

CHAPTER FIVE

“You want a cup of coffee?”

Doc Waterman was playing host to three police guests on Tuesday night. They were at Doc’s house just after seven thirty p.m. on November 17, 2004. Sergeant Randy McPherron’s face gave Doc the answer.

“Drinking coffee all day, huh?” asked Waterman.

“Yeah,” said McPherron, “that’s the last thing I need.”

The sergeant had arrived with Troopers Bob Claus and Dane Gilmore to conduct what he had told Doc on the phone earlier in the day would be routine interviews in the murder investigation. New information had come to light in the last two days and the investigators had follow-up questions for Doc and Rachelle to fill in the gaps.

McPherron would later acknowledge he hadn’t been truthful, leaving out his belief that Rachelle knew more about her mother’s murder than she was saying. The new information came from Rachelle’s friends and related to what seemed to be her suspicious behavior the last two days and additional details about problems with her mother.

“Did you wanna talk to me first?” asked Doc.

“What we like to do is maybe divide things up,” said McPherron, “have Dane stay here and talk with you and have Rachelle come with me.”

The sergeant introduced Gilmore, saying he was sent in fr

om his post in Soldotna. Doc recognized him from when the trooper spoke to the Pierces next door.

Doc said, “OK.”

Then, to Rachelle, McPherron said, “How ya doin’?”

Rachelle said she was doing fine, and McPherron asked Doc if it would be all right to interview Rachelle at the police station this time.

“I’ve talked with her about it,” said Doc. His daughter agreed.

“Super,” said McPherron. He gave his cell phone number to Doc and said, “If there’s a problem, just give me a call. We just wanna go down there and talk. We’ll be out of the way and private. Nobody will bug us.”

Doc again said, “OK,” accepting McPherron’s explanation. It was another piece of deception, McPherron actually wanting Rachelle alone, isolated, and uncomfortable—without her father or a lawyer. By law, McPherron only needed Rachelle’s permission to speak to police without her father, but the sergeant again didn’t want to tip his hand.

Rachelle put on her shoes and jacket and got into the patrol car, where McPherron reminded her to put on her seat belt for the short ride to the Craig police station.

McPherron radioed the dispatcher “10-6”—code for “I’m busy, don’t bother me”—and gave his location as 602 Ocean-view. Overhearing, Rachelle corrected him, “You know this is 604, right?”

“Six-oh-four, right,” said McPherron.

“Yeah,” said Rachelle, “I thought you said 602.”

“Oh, did I?”

“Yep.”

They drove down the hill and in the next mile passed the major landmarks of Rachelle’s fifteen years: the marina where Brian Radel kept his boat, the T-shirt shop where Rachelle once worked, the junior high school, Papa’s Pizza, the Thibodeau Mall where Brian had his computer shop, then up another hill toward the little brown police building on Second and Spruce streets.

Along the way McPherron made small talk, telling Rachelle, “My oldest daughter’s name is Rachel. So I’ve been having a hell of a time. Every time I would try to write your name, I write R-A-C-H-E-L.”

“Yeah, Rachelle is a French version of Rachel,” she said.

“Do you speak French?”

“A little bit, because we had a foreign exchange student here last year with a friend of mine.”

“That’s the one living with the Clauses, right? Bob’s daughter?” asked McPherron. The trooper had told him of the French exchange student.

“Yeah,” said Rachelle, and McPherron said, “Wow, that’s cool.” Rachelle said she was planning to go Germany next summer—the trip her mother had been raising money for with friend Janice Bush at church—and McPherron asked if Rachelle spoke German. She said she didn’t but wasn’t worried because “everyone in Europe, you know, speaks English.”

They talked about foreign languages and colleges; McPherron said his daughter was at the Art Institute of Seattle and that “I’d like to see her come back to Alaska, ’cause I miss her.”

They pulled into the back parking lot reserved for police cars, got out, and met Claus. They entered through the rear door and went down a hallway past the glass window to the left that opened to the dispatch center, where Jason’s mother worked, and into the squad room. Chief See’s office was located on the right, and down the hall was a waiting area where the front window to the dispatch office was located on one side and the DMV office on the other.

They went another few feet into a meeting room on the left.

“Why don’t you grab a seat there, make yourself comfortable,” McPherron told Rachelle. “You need a glass of water?”

“I’m fine, thanks.”

McPherron left her in the room a minute while he discussed with Claus the recording system in the room. The room was small, windowless, claustrophobic, and wired for video, which was how McPherron wanted it. His patrol car banter with Rachelle was all a calculated effort to build trust and rapport, softening Rachelle for an interview that could likely turn nasty quickly.

The investigators returned and took their seats, old family friend Claus next to Rachelle and McPherron across from them. Claus placed his digital recorder on the table, as did McPherron, so they’d have an audio backup to the video recording from a wall-mounted camera.

For the benefit of the camera, McPherron announced the time in military fashion—“1947”—and said he was “10-6 at the Craig Police Department” with Rachelle Waterman and Trooper Claus.

He looked at Rachelle.

“You can call me Randy, you know,” he said.

“Randy?”

“Yeah, we don’t need to be real formal here. And I believe you know this guy,” he said, pointing to Claus.

“Yeah,” she said.

“And I do need to record our conversation, OK?” he said. “Not a real good note taker. I wanna make sure I get everything.”

The note-taking remark was another fib: he wanted an on-video acknowledgment from Rachelle that she was aware she was being recorded; otherwise he would have needed a warrant for a secret recording. He also wanted to memorialize anything she said to use against her in court, if necessary.

With the small talk over, McPherron began the interview in earnest. He explained that since they had last spoken the night before, he had come up with “a laundry list of questions” about her mother’s “behavior” and “her lifestyle.”

“The fancy term for it is ‘victimology,’” he said. “Kind of give me a general description of her. I mean: What is she kind of like? Is she conservative?”

“Conservative in some areas,” said Rachelle. “I would say conservative to more old-fashioned.”

As she had the previous night, Rachelle spoke of her mother in the present tense. She said her mom “has a very good temper,” that “she’s usually pretty happy” and “she volunteers a lot.”

“She used to smoke like a long time ago. She drinks socially,” said Rachelle—a wine cooler at most when friends drop by. “She’s not a bar hopper or anything like that.”

McPherron asked about Rachelle’s relationship with her mother. “It’s pretty good,” said Rachelle. “I mean, we have our normal teenage mother-daughter stuff. She doesn’t like my black fingernail polish.”

The sergeant had been briefed on Rachelle’s new fashion sense from Claus and from the interviews with her friends, the black clothes and studded leather collars she had been wearing for about a year now. He didn’t press the issue yet, allowing Rachelle to speak.

“We have a good relationship,” she continued. “We talk actually a lot compared to what I know about my friends and their mothers … . I do confide in her.”

Her mother’s relationship with her father was similarly good “as far as I know,” though she had “heard rumors” of infidelity by her dad. But it was only a “hunch” and there could have been an innocent explanation, she said.

“I think maybe my dad was just, you know, going out, staying really late at work more than normal, going out for long drives that he just kind of started up the last few months,” she said. “He hasn’t really done that before … . Just off behavior for him.”

As for her mother’s routines, Rachelle said she always left the house carrying a medium-size purse bought from JCPen-ney along with a matching checkbook-size wallet. Her purse normally contained keys, checkbook, tissues, and makeup.

“She wears her [jewelry] during the day but she takes it off when she gets home,” Rachelle says. “She puts it on, like, when she goes to school or to work.”

McPherron did all the talking in the interview; Claus watched and listened. The sergeant spoke in a low, calm voice, sometimes almost a whisper that contrasted with Rachelle’s eager-to-please voice punctuated with a nervous giggle. With each question, Rachelle appeared to build confidence. About fifteen minutes into the interview, the questions moved from her mother toward her.

McPherron asked for her e-mail address; Rachelle provided it, explaining that it was inspired by the Narcissa, her favorite flower, and the jersey number she wore f

or basketball and volleyball.

Still positioning himself as Rachelle’s friend, McPherron shared that his wife’s e-mail was a mix of words created because her maiden name was Fisher and because as a child she moved nine times all over the state.

“That’s clever!” said Rachelle.

She said she was more computer savvy than her mother. Asked if her mother sent instant messages, Rachelle for the first time showed a flash of sarcasm. “She doesn’t know how to save a picture off her file: How could she figure out how to chat?”

McPherron used the computer questions to throw the first curve. “You know, obviously we’ve gotten your computer,” he told her. “We need to look through the files on the computer. We’re just looking for any information we can find that may help us find out what happened.”

He asked for her computer password.

“‘Craigsucks,’” said Rachelle. She added nervously, “Really funny.”

Asked what she used her computer for, she said she stored “pictures, hand drawings, schoolwork, music, and games.” McPherron noted that he had a search warrant to check the computer, so if there was anything embarrassing, she should tell him now. She said that, no, it was only “female conversations in my chat.”

“Kind of getting back to relationships,” said McPherron, “we’ve kind of gotten some information from other sources that there’s been a little friction between you and your mother.”

“Uh, a little,” said Rachelle. “Just over this and that.”

“Like, what are the bones of contention?” asked McPherron.

“Uh, that Jason fellow,” she said. “Like, we were friends for a while. We had kind of talked about being together, but I don’t—it’s depending on who you’re asking.” She went back to sarcasm. “I’ve also had four abortions, apparently, so it depends on who you talk to.”

McPherron just said, “Mmm-hmm,” and let her talk.

“And then,” Rachelle continued, “we realized that, you know, age difference. It’s too big. And then my mom found out later, and she’s, like: You’re talking to an older guy. And I’m, like: Yeah. You know, it was just kind of—she [was] a little bit shocked, I guess, that I was talking to this older guy about that kind of thing, even though it was very brief.”

Crazy for You

Crazy for You Love You Madly

Love You Madly